Liminal

Most are familiar with the archetypal stereotype of the tyrannical Asian parent forcing their children through years of rigorous classical training. Growing up half Filipino, most of the famous Asian musicians I knew and looked up to were either composers or classical performers, and even then, those were usually Asians living in Asia, not North American Asians. If you had asked me back then, I wouldn’t have been able to name a single mainstream Asian artist. Exaggerated parenting stereotypes aside, it might be true that cultural difference contributes in some degree to the lack of encouragement for Asian kids to pursue careers in the contemporary music industry. Honestly, if I had sacrificed as much as my mother did when she moved here from the Philippines, I probably wouldn’t be too keen on my children going into a field as unpredictable as entertainment either.

That being said, my mother has always been supportive of me going into music, so the stereotype is (obviously) not a universal truth. Music is as much (if not more) a part of everyday life in the Philippines as it is here, and my mother herself has been a singer since she was young. Seeing my mom perform onstage at church in my childhood was, I think, pretty integral to me being able to see myself as a performer too. But it would be an incomplete picture if I didn’t mention the influence of my dad, who was born in Toronto. Though I could look up to my mom as a singer, it was my dad, who understood more about the western music industry and had some firsthand experience working as a drummer here, who really made the idea of being a professional musician tangible to me. I really don’t know if I would have had the courage to go into music if not for some of the practical advice he had to give me.

I asked my mom what she thought about the lack of Asians in the music business. She also seemed to agree with the idea that some of it comes down to cultural differences. She suggested that Asian artists perhaps don’t fit into the business culture, or aren’t considered commercially viable because they’re seen as “eccentric” (in other words, unrelatable to the average white American). I think there’s some value to the culture argument, but I think there’s another side to it too. There’s North American Asians who have been participating in and contributing to North American culture for generations, who by this point should be considered anything but “unfamiliar” to this place. I think that we can’t neglect the fact the entertainment industry has largely been dominated by white producers, managers, and executives, who (shockingly) are biased towards people who look like themselves, thus making it pretty hard for Asians to get a foot in the door even if they wanted to.

In the last few decades however, the power dynamic has begun to shift pretty dramatically. The internet has democratized media to an unprecedented degree, and the call for representation is being heard more than ever. Asian-American labels like 88rising, not to mention the explosion of K-pop in the west clearly show that there is, and has been a market for Asian faces in music, waiting to be addressed. Last year, the biggest name in mainstream music was Olivia Rodrigo. Her debut, Sour, became a definitive album of the generation, with all three pre-release singles entering the charts as Gen Z anthems. I heard “Drivers License” along with everyone else when it obliterated the charts that year, but it wasn’t until quite a while later that I realized its singer was half Filipino. All of a sudden there was an Asian at the top of the charts, covering magazines, and flooding social media, and it was accepted. There was no controversy, no uproar about “pandering” (consider how Kelly Marie Tran was harassed about Star Wars), and aside from the usual mumbling about “industry plants” and so on, people mostly just seemed to be genuinely interested in this Filipina 17 year old appearing on Jimmy Fallon, for more or less the same reasons that they were interested in Billie Eilish a few years earlier.

A young Olivia Rodrigo with her parents (Disney Channel/Youtube)

Now, I certainly don’t want to discredit Olivia Rodrigo’s success, but there are a few things that I think might be worth noting about her rise to fame as an Asian artist. First of all, Rodrigo’s ethnicity has never really been a central focus of her image, and I think a lot of people probably don’t even realize she’s Asian, which included me (and my mom) for a long time. Having a Spanish last name and (debatably) without a strikingly Asian appearance, I would bet that a lot of people just assume she’s Latina. Cynically, I sometimes wonder if she would have been as successful if her name was Olivia Pagayonan or something, and if she looked slightly less white. While I’m obviously glad for her success, I wouldn’t jump to say that Olivia Rodrigo’s career arc means that now it’s considered marketable to be Filipino. I don’t want to be overly pessimistic; the topic of “marketable ethnicities” is a pretty nasty one to get into, and one that deserves its own conversation. Although I’m not going to get into it in detail here, I do think that everyone, during their daily intake of media, should think about how cultural trends regularly interact with exoticism and racial othering.

To address some examples of exoticism in the west, it’s hard not to talk about Japan. Filthy Frank was the subversive and intentionally off-putting internet persona of the half Japanese, half white George Kusunoki Miller, who has since made a very successful transition into pop music as Joji, with his most recent single, “Glimpse of Us,” taking off on TikTok and doing very well on the charts. The Filthy Frank Show dealt a lot with Japanese stereotypes, and ridiculing western perceptions of Japan, I think with a viewpoint that was unique to Miller as a mixed race person living in Japan. And though his later, more “serious” music as Joji doesn’t deal so much in overly Japanese aesthetics anymore, that was still the fuel that launched his career as an entertainer. And though Joji doesn’t really acknowledge Filthy Frank anymore, some of the same subject matter makes indirect appearances in both of their work. Miller has discussed how, due to his mixed race, he was considered a weird-looking Japanese guy when he lived in Japan, while in America he’s a weird-looking white guy. Where Filthy Frank (and associated characters, mostly played by Miller) made crude jokes about feeling weird-looking in Japan, Joji’s “YEAH RIGHT” expresses the artist’s low self-confidence and romantic isolation in America. If Filthy Frank was defiantly an outsider, Joji expresses the self-doubt and melancholy that comes at the other end, when the joke has worn off.

George Miller/Joji (Schön Magazine)

Another musician who has made a career largely out of drawing on her unique experiences as half Japanese and half white, is Sarah Midori Perry, vocalist of the English band, Kero Kero Bonito. KKB drew attention with their 2014 single “Flamingo,” in which Perry alternately sings in English and Japanese about self-acceptance and embracing difference, and addresses being “multicoloured” (that is, being mixed). A strong characteristic of KKB’s early music was its simplicity, both in composition and quirky lyrical themes. By extension, Sarah’s early persona was partially characterized by a non-threatening cuteness and an optimistic innocence, both stereotypes of young Japanese women. How intentional this representation is meant to be isn’t always made readily obvious in the music itself, but Sarah, Gus, and Jamie don’t strike me as clueless about what they’re doing. To me though, there seems to be three or four layers of irony overlaying a lot of what they do.

Kero Kero Bonito (The Daily Californian)

Potentially one piece of evidence for this is the way that band has evolved over time. Lyrically, Sarah has moved from semi-humorous vignettes of her everyday life, to more serious and introspective themes. “Only Acting” was the lead single from their third album, Time ‘n’ Place, and deals lyrically with the identity crisis of an entertainer, trying to figure out where the persona ends, and the real person begins. I think a lot of mixed-race people could relate to the existential confusion of where one part of you ends and the other begins, especially people who have one white parent and one non-white parent. Sometimes it does feel like I’m only acting, as either an Asian kid pretending to be white, or a white kid pretending to be Asian, and whether this is at all a part of Sarah’s intended narrative, I think it’s an interesting metaphor. In a way, Time ‘n’ Place illustrates this idea of identity crisis in its instrumentation too. Where their previous work drew heavily on Japanese aesthetics, particularly Japanese video game music, Time ‘n’ Place introduces more traditionally western sounding indie rock and shoegaze elements to the stage, producing a very unique synthesis of styles that I think is a pretty solid metaphor for the multicultural roots of the band.

I think I’ve touched the surface of a lot of different topics in this article, and that’s because I think racial identity in music is a pretty massive and varied subject to cover, and yet when it comes to being Asian (and especially being mixed), there is so little that’s been written. Because of that, it feels like there’s not a lot of vocabulary to describe our unique experiences. When I was starting this article about half Asians in music, my original plan was to identify tangibly “half Asian” characteristics of music, but I pretty quickly found that unfeasible from a cultural angle. First of all, “Asian” is an umbrella term as big as the continent, and identifying unifying characteristics seems more perilous than productive. I found it more useful to focus on the “half” part of the term, and while that’s also a pretty vague category, I found that the music is tied together by some themes. Isolation, alienation, rejection, identity, and escapism are strong themes in the music of Conan Gray, Japanese Breakfast, Mitski, Joji, Olivia Rodrigo, KKB, and others. You could say that these uncanny feelings are also pretty endemic to Gen Z in general, and, if I may be so bold, I think that’s why the mixed experience is so socially relevant right now. I feel like there’s so little said about the spaces in between what we call race, which is crazy to me, considering that we live in a country so significantly premised on multiculturalism. I’ve never been scared of not “fitting in” with the music world, even based on my race, because I think that art is one place where “weirdness” can be incredibly valuable. Furthermore, today’s social climate encourages me more than ever to believe in the value of my input, and the input of those like me. So shoutout to my fellow halfie creatives out there. You exist, and you have something unique that’s worth sharing.

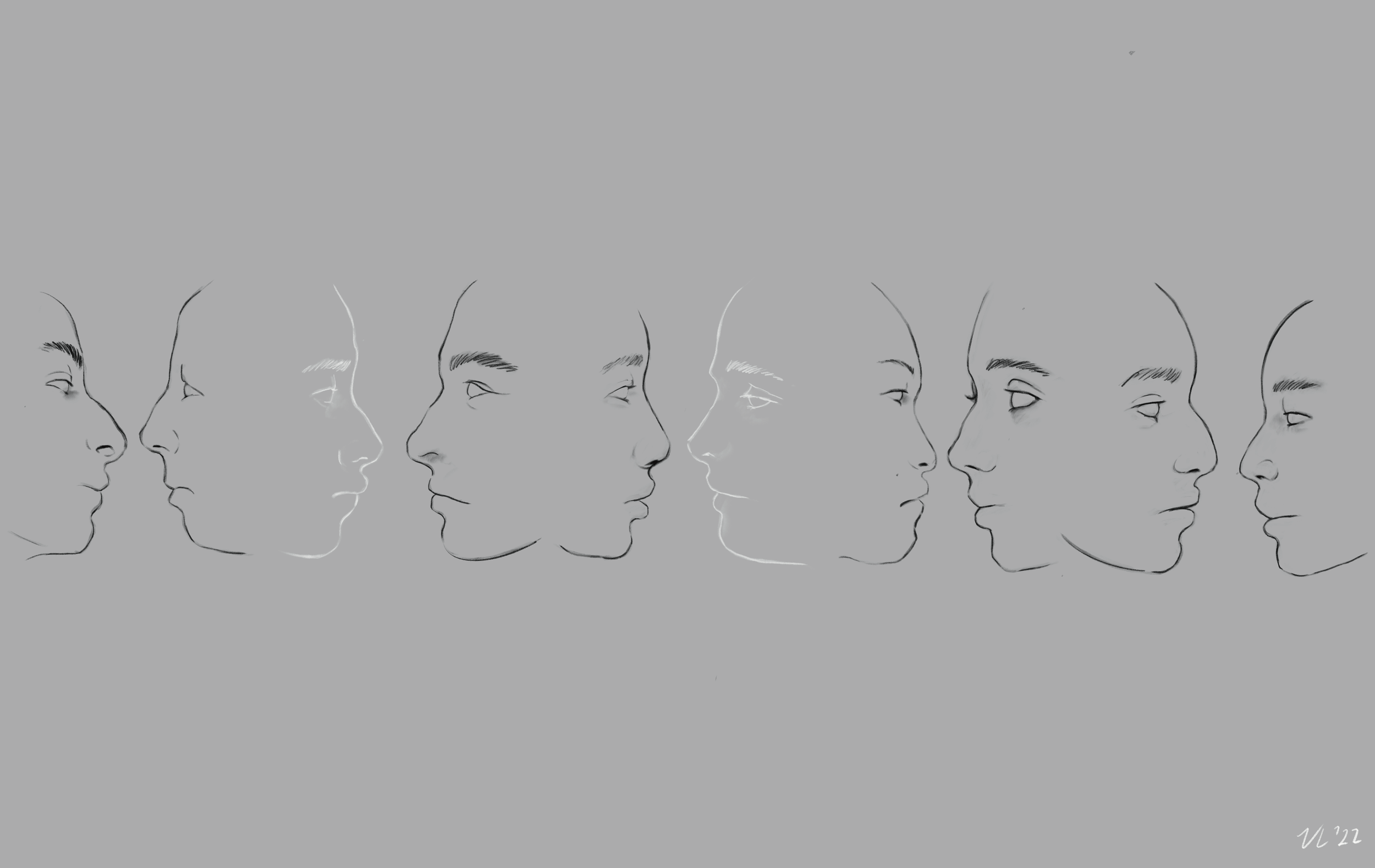

Header Image: Valerie Letts