Reevaluating My Ideas on Canadian Identity

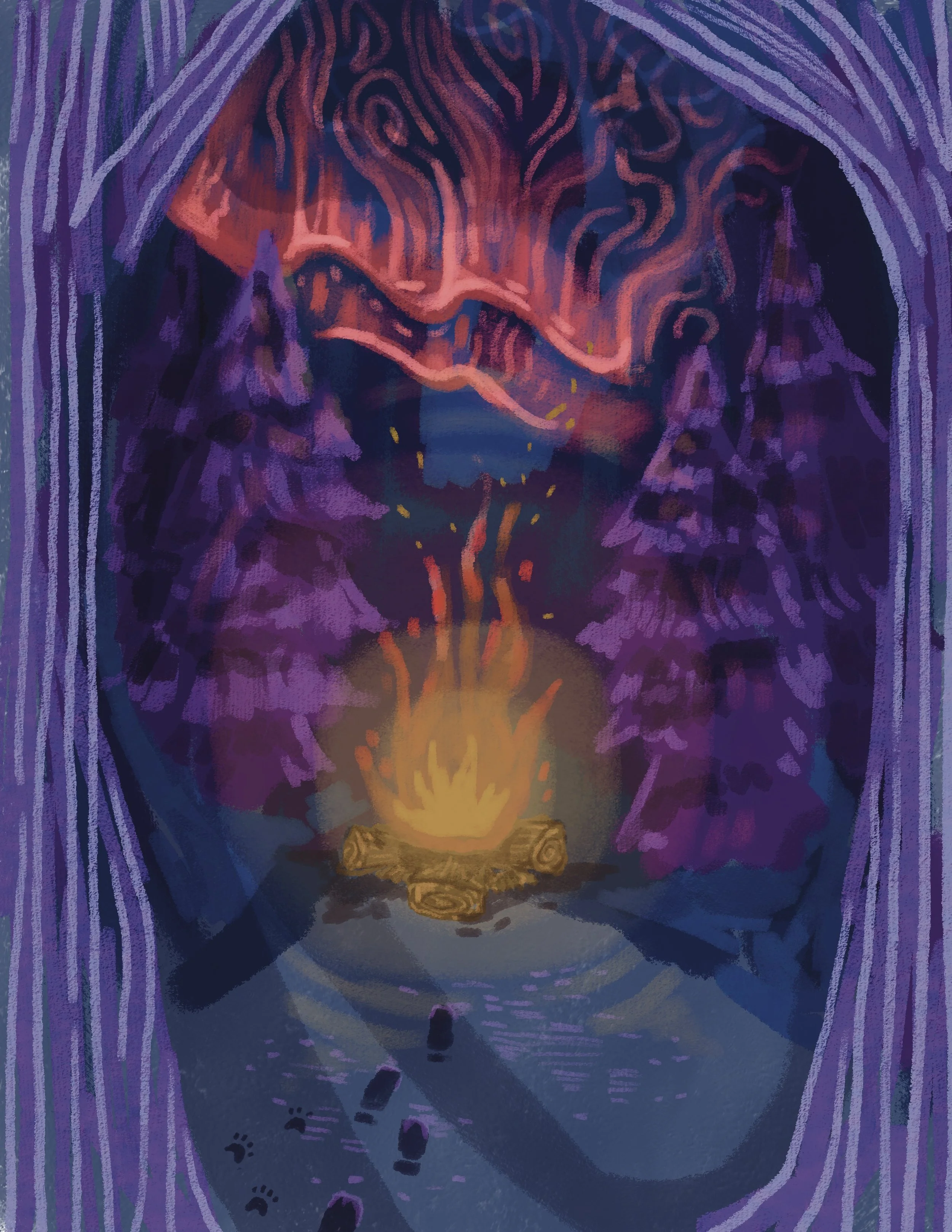

Illustration by Baran Forootan

Over the past year I’ve found myself spending a lot of time thinking about Canadian identity.

It started last fall when I spent the semester abroad studying in Paris. During my time there, I heard from many people that, in their eyes, Canadians are the same as Americans, with a few minor differences—that we are generally more polite, more progressive and softer spoken. Around that same time, Trump began making threats to annex Canada, which led me, like many Canadians, to ask existential questions about our country. What makes us a nation? What are our values? What makes Canada worth fighting for?

As I asked myself these questions, I thought about the common ideas that we hear about Canada. We are one of the only countries to successfully maintain and protect a linguistic minority within a single nation. We are a country of multiculturalism and diversity, known around the world for welcoming immigrants with open arms. We have a distinct cultural heritage—a unique blend of British, French, and Indigenous influences, symbolized by the maple leaf, poutine, and hockey. But all of these ideas feel like characteristics of our country that we cherish rather than reasons why we, as a people, are distinct and worthy of our own nation.

I think many Canadians experience somewhat of an identity crisis when it comes to evaluating our national identity—for two main reasons.

First, Canada’s multiculturalism makes it hard to determine what is uniquely Canadian. Since the earliest days of Canada, immigrants have arrived with their own beliefs, worldviews, and traditions. And as opposed to America’s “melting pot”, where immigrants are expected to assimilate into American culture, Canada is largely considered to be a “cultural mosaic” where immigrants are encouraged to maintain their own cultural identities. For many Canadians, this makes it hard for us to decipher what parts of ourselves are distinctly Canadian, and what parts of ourselves we inherit from our family origins.

Second, our proximity to America, both geographically and culturally, creates a Canadian culture that is nebulous. Mediums that are used to shape culture—television, radio, newspapers—are often shared and syndicated across the border. Canadian musicians, writers, actors, and filmmakers often move to the U.S to collaborate with American counterparts, leading to albums, films, and television that are rarely identified as being distinctly Canadian. Cultural phenomena that are ideated by Canadians—Saturday Night Live, Drake, even this summer’s K-Pop Demon Hunters—end up being perceived as part of America’s cultural empire. In this sense, we are contributors to a global cultural influence for which we never really receive full credit.

In the absence of a clear and singular cultural identity, we ask ourselves what defines the Canadian psyche.

I’ve always thought that Canadian identity is tied closely to the climate—that the cold, harsh winters have forced us as Canadians to look after one another in ways that our American friends, with their more temperate climate, have not been forced to do.

I recently discussed this topic with a professor at Queen’s, who pointed me to differences in the founding documents of Canada and the United States. He told me that while America’s constitution calls for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Canada’s constitution calls for “peace, order and good government.”

I think this too is closely tied to the climate. In Canada, early settlers were hit with a winter every year that threatened their existence as a settlement and their ability to continue inhabiting the land. Inevitably, there was an immense amount of unity and harmony required to survive. In these circumstances, I believe Canadians developed an identity rooted in empathy, groundedness, and sacrifice for the common good. Canadians, unlike our southern neighbours, learned early on that if we were to go it alone, we would be powerless. This is still, to a great extent, intact in our collective consciousness, visible in our politics, our social safety net, and the art that we produce.

Famed Canadian author Margaret Atwood touches on this idea in her 1972 survey of Canadian literature, where she identifies “survival” as the unifying symbol of Canadian culture. European explorers who first arrived in Canada had to survive against the harsh climate. French Canadians had to survive culturally when the British conquered New France. And we as Canadians have had to survive as an independent nation as our southern neighbours have become the world’s most powerful economic and cultural power.

Atwood says that this notion of survival creates not a sense of “adventure,” as in the American frontier, nor a sense of “smugness and comfort,” as with Britain’s isolation on an island, but an “intolerable anxiety,” in which Canadians are constantly aware of what it takes to maintain their survival as a people.

I think this constant anxiety around survival makes Canadians highly conscious of the fragility of our collective existence and fosters a strong desire for order and social harmony, both at home and abroad.

We see this expressed in cultural works produced by Canadian artists and writers. Joni Mitchell’s 1970 song “Woodstock” paints an image of “bomber jet planes” turning into “butterflies” against the background of the Cold War. Neil Young’s “Southern Man” critiques Bible-thumping Southerners and Klansmen for their violent acts of white supremacy. Margaret Atwood's own The Handmaid’s Tale offers one of contemporary literature’s starkest warnings about the regression of women's rights and dangers of totalitarianism.

This desire for order and harmony may explain why Canada, despite being so culturally similar to America, has, at least for now, been spared from the democratic erosion and political violence that have in recent years come to haunt our southern neighbours.

It may also explain why so many have fled to Canada, escaping war, discrimination, and slavery in search of a land that values stability and fairness.

In a world where many nations endorse unnecessary chaos and conflict, we Canadians—having been brought face to face with nature’s harshest elements—recognize how fragile our societies truly are. Peace, order, and harmony are vital to our collective survival. To me, this is what makes us Canadian, and why our country will always be worth fighting for.